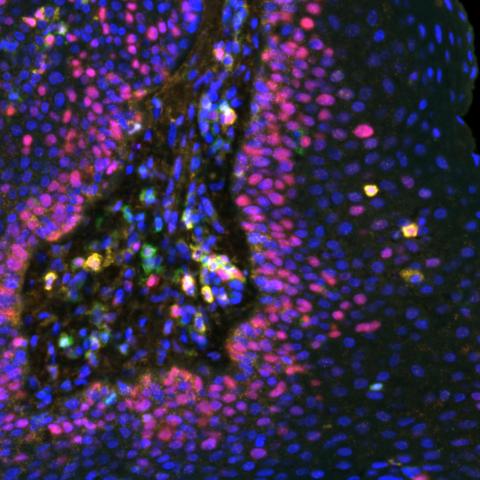

Multispectral immunofluorescence image of a respiratory papilloma stained for various biomarkers: Ki67 (red), CD8 (Gold), CD4 (green) and PDL1 (orange). Image credit: Allen lab.

A phase I clinical trial testing an experimental vaccine for recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP), a condition marked by frequent growths in the airways caused by a chronic human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, found that growths stopped in about half of patients who received treatment. The results were reported October 25, 2023, in Science Translational Medicine.

More than 10,000 adults are living with RRP in the United States. The disease, which is treated with frequent surgeries to remove abnormal growths in the airway, leads to dangerous breathing problems and bothersome voice quality changes. On rare occasions, RRP growths can turn into cancer.

Some patients require hundreds of surgeries over their lifetime, explained Scott Norberg, D.O., Associate Research Physician in the Center for Immuno-Oncology, who co-led the study with Clint T. Allen, M.D., Senior Investigator in the Surgical Oncology Program. “When you are young and diagnosed with RRP, it defines your life afterwards,” he continued.

Previous attempts to design new treatments for RRP focused on unleashing an existing immune response against HPV-infected cells. That approach doesn’t work, Norberg explained, because many patients lack ample immunity towards the virus.

In contrast, the experimental vaccine trains T cells in the immune system to recognize and kill HPV-infected cells — specifically cells that are infected with HPV-6 or HPV-11, the underlying cause of RRP. In the current study, 15 adults with RRP received four subcutaneous shots of the vaccine, one shot in each arm and leg, during a three-month window of time.

With the vaccine, about half of the patients avoided any type of surgery for RRP in the year following the treatment. In the year prior to vaccination, that group of patients had undergone a median of six surgeries for new growths. The most common complaint from the vaccine was temporary soreness at the injection site, but no serious side effects were reported.

The researchers found that patients who had the best response to the vaccine had high levels of certain small proteins, called chemokines, that attract cancer-fighting T cells to the growths. Patients with growths that continued to form tended to have high levels of other chemokines that are known to repel T cells. This “chemokine switch,” Norberg explained, is an important piece of the puzzle to identify additional treatments to help all patients receive a benefit from the vaccine.

“This work is important because it identifies a completely new treatment for RRP that is safe and appears to be effective in a high proportion of patients,” Allen said. If the vaccine works well in additional studies, he continued, “this could change the standard of care for adult patients with RRP and give them hope that has not been present for many decades.”

The clinical study was sponsored by Precigen and conducted by the CCR team under a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA).