Protein TP53

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Researchers in the Center for Cancer Research have found that circulating lymphocytes can be stimulated in the laboratory to generate cells that can recognize TP53 gene mutations. Mutations to the TP53 gene are found in about 40 percent of all cancers, making this process a potentially significant step forward in fighting many types of cancer. The research, conducted by Steven A. Rosenberg, M.D., Ph.D., Chief of the Surgery Branch, Parisa Malekzadeh, M.D., Drew C. Deniger, Ph.D., and colleagues appeared January 29, 2020, in Clinical Cancer Research.

Effective drugs that directly target TP53 mutations have been sought for decades with minimal success. Targeting TP53 is important because the non-mutated TP53 protein can act as a tumor suppressor by causing cell death if it detects damage to a cell.

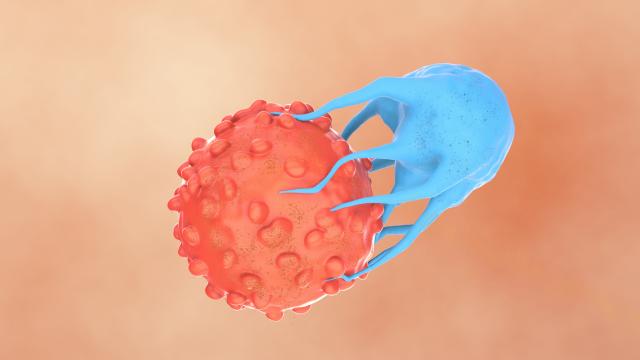

Rosenberg’s group has shown that one type of treatment approach, adoptive cell therapy, can lead to complete tumor regression in some patients with common solid cancers. The reason the approach can work, Rosenberg says, is due to the recognition of mutated neoantigens that are usually unique to each person’s cancer and can thus be targeted by specific receptors on the surface of T cells. Molecules that trigger an immune response are known as antigens; neoantigens are newly formed antigens, resulting from DNA mutations in the cancer and recognized by the immune system.

Based in part on the adoptive cell therapy model, using lab methods, the researchers stimulated precursors of lymphocytes that occur naturally at levels generally below one in 1,000 and can be expanded in the laboratory to levels as high as 70 percent. They focused on stimulating the lymphoid precursor cells that circulate in peripheral blood and thus are more easily accessible than cells such as difficult-to-extract tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes used in adoptive cell therapy or T cells that must be modified with anti-tumor receptors.

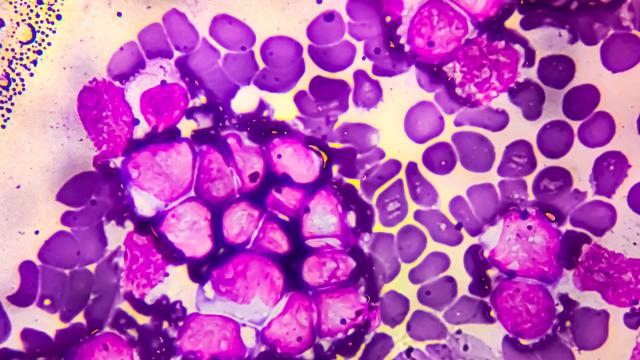

After isolating peripheral blood lymphocytes, or PBLs, from people with TP53 mutations, the scientists then stimulated their PBLs with TP53-expressing cells in the laboratory. PBLs from seven colon, one rectal and one ovarian cancer patient with TP53-mutated tumors were examined. T cells which recognize TP53 mutations were found in antigen-experienced T cells from PBLs of five patients but not the other four, most likely because of the very low frequency of p53 reactive cells in the blood of those four patients.

“Ultimately, if we could identify lymphocytes that recognize TP53 mutations in blood drawn from a patient, PBLs could be an ideal source of T cells used in adoptive cell therapy for a variety of cancer types,” said Rosenberg.