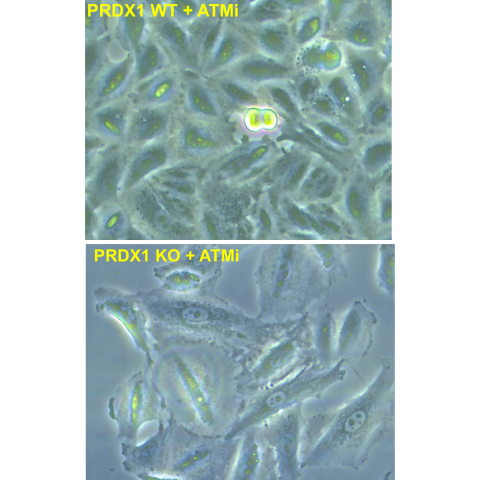

Top: non-small cell lung cancer cells A549 treated with an ATM inhibitor drug. Bottom: non-small cell lung cancer cells A549 lacking PRDX1 and treated with an ATM inhibitor drug. CREDIT: Haojian Li et al.

Researchers have identified a new combination for targeting cancer cells that dramatically boosts tumor response to chemotherapy in mice. The results, which early findings suggest may apply to humans, were published January 19, 2025, in Redox Biology.

Standard chemotherapies generally work by causing significant DNA damage to cancer cells, which increases the chances of the cells dying. It is known that a protein called ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase can help repair damaged DNA and may help protect cancer cells from the effects of chemotherapy. As a result, several drugs that inhibit ATM are being tested in clinical trials with the hope that they will complement the cancer-killing effects of chemotherapy.

Urbain Weyemi, Ph.D., Stadtman Investigator in the Developmental Therapeutics Branch, notes that decades ago scientists thought that hitting just one survival pathway of cancer cells would be enough to kill them, but learned that is not always sufficient. “Tumor cells often have the ability to activate alternative repair and survival pathways to overcome the damage induced by a drug,” he explains.

Weyemi was interested in searching for secondary pathways that cells rely on when ATM is inhibited. To do so, he and his colleagues screened roughly 3,000 genes that were likely to be regulated by ATM and homed in on one that produces a protein called peroxiredoxin 1 (PDRX1). This protein works quickly to protect cells when they are under oxidative stress, which is the case for many cancer cells exposed to chemotherapy.

Through a series of experiments, Weyemi and his colleagues showed that cancer cells treated with an ATM inhibiting drug could survive DNA damage, but they are much less likely to survive when PDRX1 is also inhibited.

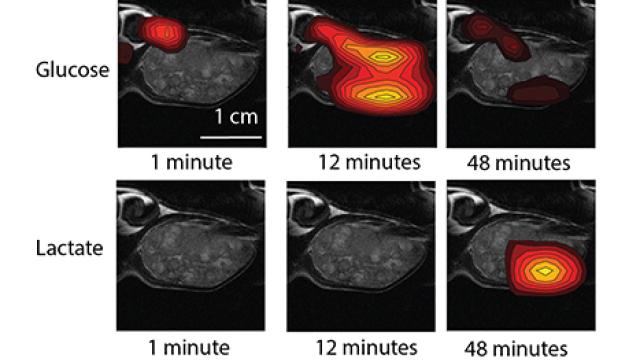

For example, the researchers developed lung cancer cells lacking the gene needed to produce PDRX1 and studied the fate of these cancer cells in mice. When mice bearing tumor cells that lacked PDRX1 were treated with ATM inhibiting drugs, the treatment led to a significant halt in tumor growth. As a result, these mice had over a two-fold increase in overall survival rates compared to mice injected with the same tumor cells but treated with a placebo.

To explore whether these findings may apply to humans, Weyemi and his colleagues analyzed data from The Cancer Genome Atlas, which has cataloged an extensive array of mutations to dozens of different types of cancer. The results suggest that similar effects may be at play in humans.

“What we found is that there is a correlation between ATM and the expression level of PDRX1 in people,” Weyemi says, noting that patients who had high levels of both tended to have aggressive tumors and shorter survival periods, whereas patients with low ATM and low PDRX1 tended to live longer.

Weyemi also noted an interesting find in the study: in both petri dishes and mice, cancer cells lacking ATM and PDRX1 were only likely to die if they also had an activated cell survival pathway called p53-mediated cell death. Normally this gene pathway protects cells from turning cancerous, but some cancers have mutations in p53 that allow them to persist anyways. This means that patients whose cancers have a non-mutated, functional p53 gene pathway may benefit from chemotherapy in combination with ATM and PDRX1 inhibition, if these findings translate to humans.

Weyemi says he is interested in expanding upon this work to explore, at a broader level, how various cancer cells sense oxidative stress to protect their genome from chemotherapy.