Faced with the burgeoning HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, NCI’s intramural program developed the first therapies to effectively treat the disease. These discoveries helped transform a fatal diagnosis to the manageable condition it is for many today.

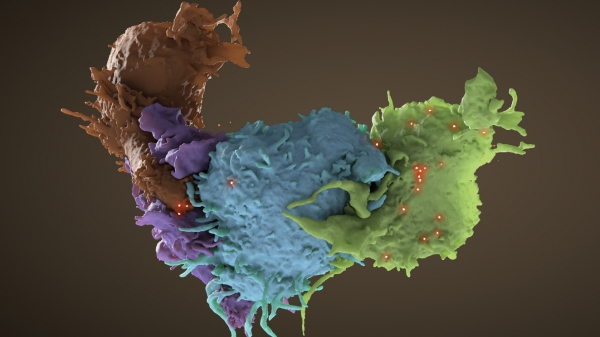

An HIV-infected T cell (blue, green) interacts with an uninfected cell (brown, purple).

Credit: Donald Bliss, National Library of Medicine, NIH; Sriram Subramaniam, CCR, NCI, NIH

Faced with the burgeoning HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, NCI’s intramural program developed the first therapies to effectively treat the disease. The NCI efforts drew upon its established expertise in virology, tumor biology and the immune system and was enabled by the inherent flexibility of the NIH intramural research program to respond quickly to new crises. The discoveries of NCI researchers in the early days of HIV/AIDS were vital in transforming HIV infection from a fatal diagnosis to the manageable condition it is for many today.

Patients with the mysterious immune disorder now known as AIDS had been arriving at the NIH Clinical Center since 1981. When the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was identified by Luc Montagnier, M.D., at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, and then shown by NCI’s Robert Gallo, M.D., in 1984 to be the cause of AIDS, NCI scientists were poised to rapidly act on the discoveries.

At the time, there were almost no effective antiviral drugs for any disease, and it was unclear whether stopping HIV from replicating was feasible or would allow patients’ immune systems to recover from an infection. But NCI’s Samuel Broder, M.D., Hiroaki Mitsuya, M.D., Ph.D., and Robert Yarchoan, M.D., searched for compounds that inhibited viral growth in the laboratory and then immediately initiated first-in-human trials at the NIH Clinical Center to test them in patients. NCI’s strong industry collaborations helped speed patient access to the new drugs.

The NCI researchers first focused on a viral enzyme called reverse transcriptase that HIV needs to multiply. They developed an assay to test the utility of drugs against HIV and gathered a number of promising compounds to test. Azidothymidine (AZT), a compound first synthesized by Jerome Horowitz, Ph.D., in 1964 as an anti-cancer drug, was among the drugs initially tested. In a preliminary clinical trial done largely in the NIH Clinical Center, NCI scientists showed that AZT could improve the immune function of AIDS patients. In a randomized trial, it was subsequently shown to improve survival of AIDS patients. In 1987, it became the first drug approved by the U.S. FDA for treatment of the disease. AZT was subsequently shown to markedly reduce the perinatal transmission of HIV.

Because AZT was not entirely effective by itself, NCI scientists continued to develop and test other drugs to treat AIDS, including the reverse transcriptase inhibitors didanosine (ddI) and zalcitabine (ddC). These became the second and third drugs approved by the FDA for AIDS. Combining AZT with one of these drugs improved the effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy.

Unfortunately, patients often developed resistance to these drugs. As researchers learned more about HIV in the following years, they were able to develop drugs that attacked the virus in new ways. NCI scientists helped map out the structure of another essential viral enzyme, the HIV protease, to guide the design of a new class of HIV drugs. When combined with reverse transcriptase inhibitors, protease inhibitors, developed in the mid-1990s, dramatically suppressed replication of the virus, often reducing it to undetectable levels.

The number of AIDS-related deaths in the U.S., which exceeded 40,000 in 1995, declined rapidly after the introduction of this combination therapy, called highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). HAART has dramatically reduced AIDS mortality and transmission of the virus in many parts of the world where there has been ready access to the medication. It has also markedly reduced the development of the many AIDS-related cancers that are associated with immunodeficiency. CCR scientists have continued to study the virus, including malignancies such as Kaposi sarcoma that are related to and influenced by HIV infection, and patients living with HIV today have even more treatment options.

Reference

- Yarchoan R, et al. Lancet. 1987;1:132-5.

- Yarchoan R, et al. Lancet. 1988;1:76-81.

- Yarchoan R, et al. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(11):726-38.

- Yarchoan R, et al. Science. 1989;245(4916):412-5.

- Miller M, et al. Science. 1989;246(4934):1149-52.

- Jacobo-Molina A, et al. PNAS. 1993;90(13):6320-4.

- Koh Y, et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(10):3123-9.